By Kamalika Ghosh

At the peak of liberalisation in the 90s, most households were opening themselves up to the world. Except for mine, which remained doggedly as inward as it could manage. So while people were welcoming cable television, my typically Bengali grandfather wouldn’t allow it inside our home for the longest time.

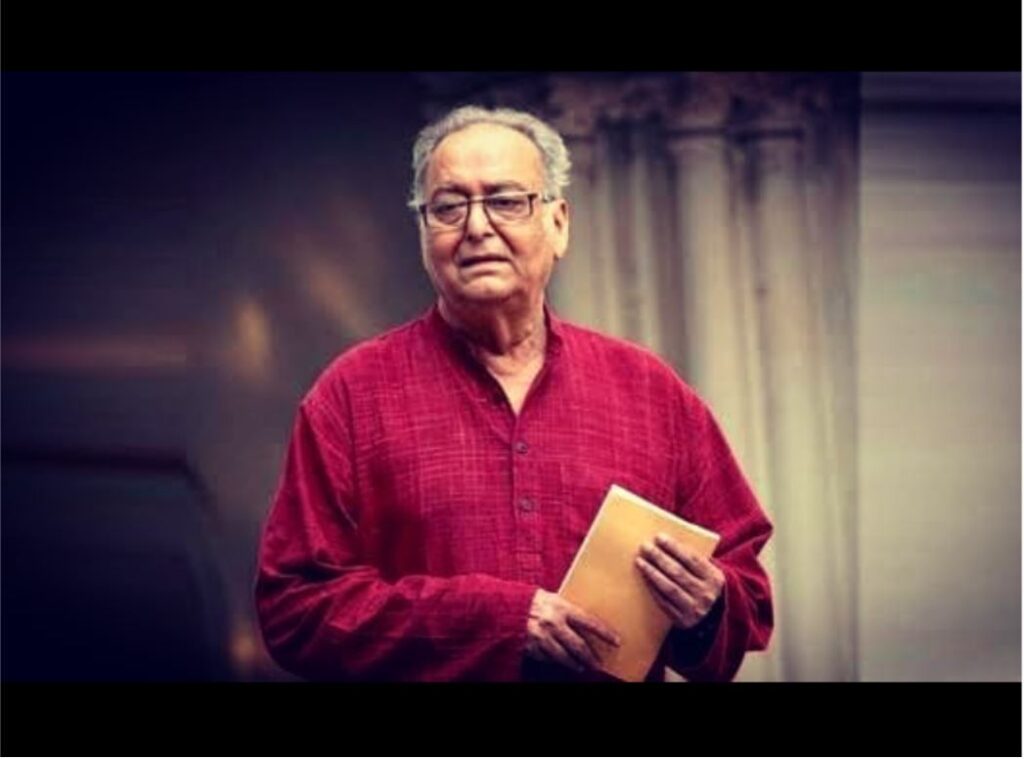

And much like the film Jhinder Bondi, Soumitra Chatterjee as an actor too was the anti-thesis to Uttam Kumar. In most of his early collaborations with Satyajit Ray, like Devi or

Teen Kanya, Ray stripped his male lead of the traditional “masculinity” in both the films, both of which were much more about the female protagonists. But Chatterjee immediately endeared to an audience overfed on Uttam Kumar.

Uttam Kumar was the hero every woman wanted as a husband. But Soumitra Chatterjee’s Apu was the husband most of the women ended up having. Soumitra Chatterjee had an easy charm and likeability, much like Uttam Kumar. But there was something that Chatterjee had in generous amounts but Kumar fell short of.

Soumitra projected on screen an inner vulnerability. And in his debut film, Apur Songshar, that vulnerability seared through the surface in his portrayal of the grief of losing his wife to childbirth. Apu takes his pain and helplessness out by not only abandoning his child but also in distancing himself completely from the idea of a home.

This vulnerability lent a poignancy to every scene from Apur Shongsar. While every woman in my mother’s and grandmother’s generation swooned at the sight of a pipe-smoking Uttam Kumar on screen, but off it, they were all Sharmilla Tagore’s Aparna from Apur Songshar, telling their husbands to cut down smoking. There are very few scenes in Indian cinema as endearing and intimate as the one in which Soumitra finds a note pasted by Sharmila on his cigarette packet saying: “Khawar pore ekta kore — katha diyecho (You promised not to smoke more than one after meals).

His dedication to the craft was such that he became the characters he essayed. It’s very difficult to say where Soumitra ended and where Apu (Apur Songshar), Feluda (Joybaba Felunath and Sonar Kella), Lear (he enacted King Lear on stage), Amal (Charulata), and countless other characters begun.

Some of his finest performances were in non-Ray films. In Ajoy Kar’s Saat Panke Badha he is cast opposite the reigning superstar of Bengali cinema, Suchitra Sen, as a headstrong husband obstinate about his sense of right and wrong, even when his marriage crumbles. The film’s narration bats for the female lead, almost admonishing Chatterjee’s character for not paying heed to the needs of his wife. Chatterjee holds forth even in front of Bengal’s diva, as the toxic husband but at the same time humanising the character.

For the longest time, heroes of both commercial and parallel Bengali cinema weren’t “macho.” Its heroes were soft, affable, charming. But despite being “softer” than their then Hindi counterparts, Bengali heroes were hardly without their male egos. And Soumitra Chatterjee personified this “soft masculinity” with his easy appeal, razor-sharp intellect and the deep, piercing gaze.

In a brilliant memory game sequence in Aranyer Din Ratri, Ray put in sharp focus the Bengali male ego. Soumitra’s Asim and Sharmila’s Aparna are the only ones left in the game and the sequence closes with Aparna giving up and deliberately handing victory to Asim. Asim had placed his entire confidence at stake on a win in the game.

Bengalis strangely are a species obsessed with binaries they themselves create. Like East Bengal v/s Mohan Bagan, Ilish v/s Chingri Uttam v/s Soumitra, Feluda v/s Byomkesh, and so many of such mindless but delightful binaries.

And unlike my mother, I have no qualms in admitting that though I have tried to figure out the enigma that Uttam Kumar was, but I have always been camp Soumitra Chatterjee.

After the curtains drew on the best phase of Bengali cinema, with Ray, Tapan Sinha, Mrinal Sen, Ajoy Kar, Dinen Gupta and Ashutosh Bandopadhyay either passing away or choosing to not make cinema anymore, the Bengali film industry couldn’t do justice to Chatterjee’s genius. From the 80s till recently, the Bengal film industry was trying to grapple with the brilliance that Chatterjee was. Clearly, Chatterjee was much above the league of the industry he inherited in the post-Ray-Ghatak-Sen-Sinha era.

Probably because of his immortal association with Satyajit Ray, who adapted so many of Rabindranath Tagore’s and Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s works in cinema, Chatterjee became somewhat of a link to the last of the men from Bengal’s Renaissance. From theatre to being a poet, an actor, a director, an activist, an elocutionist, Chatterjee had one head and hundreds of hats.

Apart from the actor Soumitra, it was the activist Soumitra that left a lasting impression on me. He represented the last of the public figures who didn’t shy away from putting their politics out there. His personal life was subject to a number of tragedies and losses. He refused to warm up to his ideological adversaries once the direction of the winds changed. This faith in his own value system and the life that he lived, has perhaps been best summarised in the lyrics of one of his superhit songs. It’s as if he welcomed death singing:

“Jodi shob chariye, duti haath bariye,

Harabar khushi te, jai sudhu hariye.

Jete jete karo bhoy thomke darabo na.

(If I move beyond everything, and with open arms,

Keep getting lost in the happiness of being lost,

And while going, I won’t stop out of fear of anyone).”

The writer is a Delhi-based journalist.